Remembering

Respecting Our Fallen

He was cold; he was destitute; he was homeless; on that miserable winter’s night in January 1908 he lay slumped in a freezing Montreal doorway. Disregarded by the two policemen who found him as just another drunk who needed to sleep it off, Trooper James Daly was summarily shipped to the general hospital. It was only when orderly Arthur Hair happened to find Boer War discharge papers in Daly’s jacket that anyone began to take notice. The blue envelope was his only possession, albeit a proud one, after serving King and country for more than 20 years. Trooper Daly was no drunk: he was in the depths of hypothermia and malnutrition, and he died two days later at the age of 53.

He was cold; he was destitute; he was homeless; on that miserable winter’s night in January 1908 he lay slumped in a freezing Montreal doorway. Disregarded by the two policemen who found him as just another drunk who needed to sleep it off, Trooper James Daly was summarily shipped to the general hospital. It was only when orderly Arthur Hair happened to find Boer War discharge papers in Daly’s jacket that anyone began to take notice. The blue envelope was his only possession, albeit a proud one, after serving King and country for more than 20 years. Trooper Daly was no drunk: he was in the depths of hypothermia and malnutrition, and he died two days later at the age of 53.

The facts of this brave soldier’s death were tragic enough, but to add to the humiliation, his unclaimed body was to be turned over to medical researchers with no regard for a veteran who served the Empire so well. Arthur Hair could not abide such disrespect, so he and his friends raised enough money to allow the Trooper to be buried with dignity in a cemetery on Mount Royal.

This encounter changed the course of Hair’s life, and with great effort and the support of Montreal’s wealthier citizens, the ‘Last Post Imperial Navy and Military Contingency Fund,’ as they called it back then, was established in April of 1909. The Governor-General became the honorary patron of the fund, and in 1921 the organization was federally incorporated and expanded its operations to cover the entire country. The first burial outside Quebec took place in Toronto in November 1922, and in 1923, the fund’s profile was further enhanced when Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, Canada’s hero of Passchendaele and Vimy Ridge, became president.

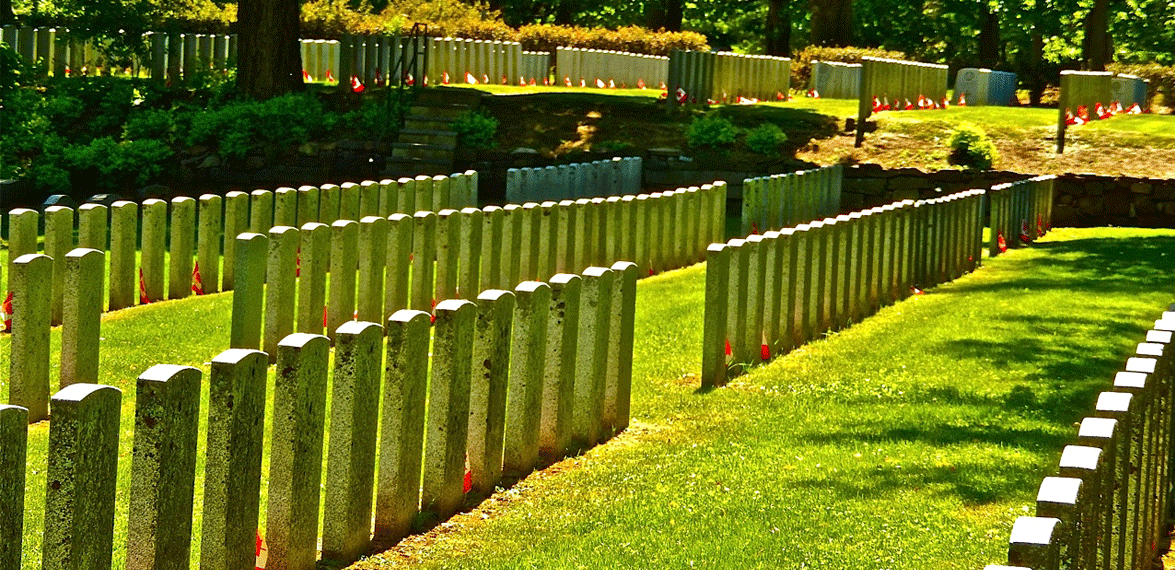

The most striking development in the 30ss was the establishment of the Last Post Fund’s Canadian Field of Honour in a large cemetery at Pointe-Claire, Quebec. During its inauguration, a major newspaper wrote that it must be “one of the Empire’s most beautiful cemeteries.” It remains so today, where it is the final resting place for more than 22,000 servicemen and women. The Field of Honour is open to all veterans of the Second World War, the Korean War, and those who served during peacetime and on special duty. Incidentally, fewer than 80,000 veterans of the Second World War and the Korean War are living today, along with some 600,000 modern-day veterans.

The LPF is mandated to deliver Veterans Affairs Canada Funeral and burial programmes for eligible Canadians and allied veterans, and its unmarked grave programme provides military markers for forgotten heroes as they are discovered. For example, thirteen sappers from the Royal Sappers and Miners of the British army who died prior to 1831 during the construction of the Rideau Canal all lie in unmarked graves. They were originally buried with wooden markers near the Newboro Lock, but on July 6, they will be recognized with a handsome marker provided by the LPF. The stone will read, “Dedicated to the members of the 7th Company Royal Sappers and Miners laid to rest while serving the British empire during the construction of the Rideau Canal 1829-31.”

Overall, an estimated 4000 unmarked graves remain in Canada alone, and the LPF continually seeks out and rectifies this unfortunate situation.

The Last Post Fund approved 1,174 applications for assistance during the last fiscal year, 445 of which were modern-day veterans. Markers for 549 veterans were approved and in all, 3,682 “lost” veterans have been identified and properly marked.

Of course, no one should be denied a respectful and decent funeral for lack of funds at the end of life, but when it comes to veterans, we owe a special debt of gratitude to those who have never hesitated to put their very lives on the line for all of us. When we support in death those who have given so much in life, we will truly find comfort in those resounding words, “At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them.”

By Col Gil Taylor (HCol ret’d)